It’s March 2022. The harshest sanctions against russia in history are being debated in government offices across the world. Every time a new package of restrictions is introduced, the prognosis for the kremlin looks progressively worse.

Russia was expected to experience a 30% drop in oil production, a 15% fall in GDP, and a 50% decline in imports. Regrettably, none of these predictions came true. Nowadays, russians mock these forecasts in the same way Ukrainians laughed at russian plans of “taking Kyiv in three days”.

Western sanctions proved to be too much of a compromise. Some restrictions were abandoned, others were not pushed hard enough, leaving many loopholes, and some were postponed for a year or even two, giving the aggressor time to adapt.

The core goal of the sanctions imposed is to force russia to end the war. War means huge expenditure, and money comes from trade. If the blows to trade are not genuinely devastating for the Kremlin, then the current sanctions policy must be profoundly changed.

It got no worse

Trade consists of imports and exports. The difference between them is known as the trade balance. The idea of sanctions is to hit the aggressor’s trade flows via reducing its exports as much as possible and limiting its imports.

In theory, russia would then no longer be able to finance the war; the government would retract their policy of aggression against Ukraine and be forced to back down. In practice, the impact that Western sanctions have had on russian trade is much less significant than the Western world would have liked.

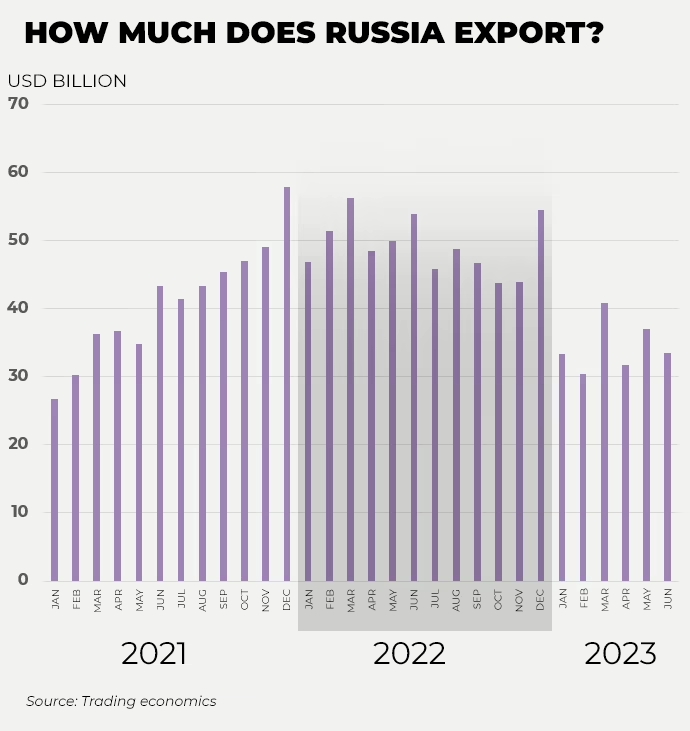

Russia’s exports did not fall in 2022, but grew by 20%. In fact, russia chose the best possible time to wage a major war – during the peak of global inflation. Global industry was recovering from COVID-19, key central bank rates were low, and everyone needed commodities, and had the funds to afford them, so prices were on the rise.

Commodity markets got a shock when russia invaded Ukraine. Stock exchanges reacted by raising the price of oil, gas, food and metals. Fearing an even greater rise in the price of commodities, Western countries postponed the application of sanctions against russia for 6–12 months.

This is how the aggressor bought time. Moscow spent the entirety of 2022 rolling in dollars. Last year, russian exports reached US$591 billion, a record high in the history of the russian federation.

Global inflation had calmed down by the end of the year, and the energy embargo finally came into effect. Russian exports took a hit. Over the first half of 2023, exports from russia fell to US$206 billion, down from US$306 billion in the same period the previous year. An immediate drop of 30%. Does this mean that sanctions have been effective? Yes and no.

Russia has actually only regressed to the pre-war export level. The aggressor generated the same amount from exports in 2019 as it did in 2021. Judging purely by numbers, the sanctions did not hurt russian exports, but rather cut off their profit increase and brought them back to 2021 levels.

If we look at qualitative indicators, the russian federation has started exporting more oil and less of high value-added goods: pharmaceuticals, cars, railway transport, furniture, etc.

This will subsequently affect the competitiveness of the russian economy and make it more dependent on commodity prices. This means that the sanctions have hit the future of some russian industries, but have not deprived the country of trade revenues overall.

Now let’s turn to imports. They are vital, as if russians keep generating money, they need to spend it on something. High-tech production, and particularly weapon production, is dependent on imports. The latter fell significantly after Western brands left the country, which mostly imported their goods into russia themselves.

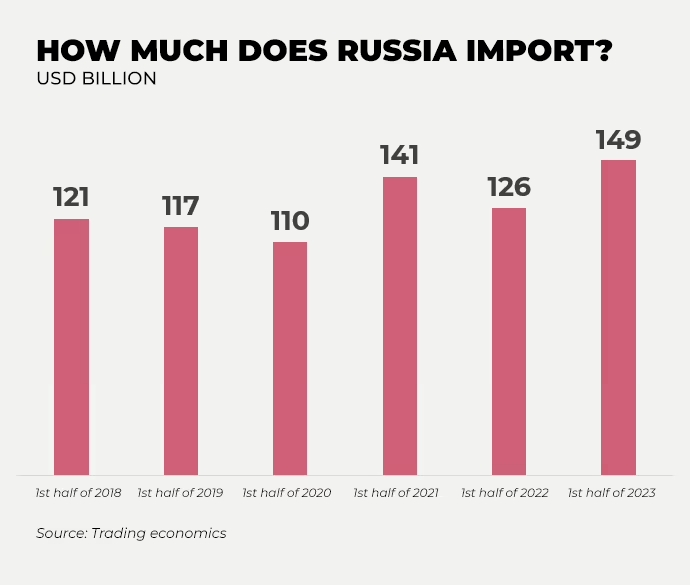

Economists expected that imports would fall by at least a third by the end of 2022. This would mean that more foreign currency would remain in the country, and the russian rouble would strengthen, causing the federal budget to lose tax revenues in national currency. On top of that, the industry will slow down due to the technology embargo.

This estimate proved to be inaccurate. Imports to russia shrank by only 13% by the end of last year. In comparison, the decline during the 2009 and 2015 financial crises was three times bigger. In the first half of 2023, russia’s imports stabilised back to the pre-crisis level of 2021.

As for the import of technological components, the sanctions performed slightly better. Comparing July 2023 to July 2021, the supply of electrical machinery and components fell by 27%, computers by 13%, tools and apparatus by 46%, and transport equipment by 70%.

The quality of these goods is likely to have suffered as well, as russia had to make up for the lost imports with Chinese-made products. However, it’s impossible to determine what proportion of these goods are actually Chinese and what is imported from other Western countries. At the same time, russia has retained its ability to produce new technological weapons, although now components take longer to arrive and cost more.

The trade balance of the russian federation amounted to US$57 billion in the first half of 2023, which is only 15% less than in the same period of 2021. Since russia still exports more goods than it purchases, the russian central bank has the opportunity to replenish its reserves.

“Russian institutions have amassed new foreign assets worth around US$150 billion throughout the sanctions regime. Although the sanctions have effectively frozen a significant portion of russia’s pre-war reserve stocks, they have not stemmed new flows,” says Professor Lidiia Lisovska, Doctor of Economics.

The russian economy is generally trending towards declining exports and growing imports. The country has less foreign currency, so the russian rouble has devalued to RUB 100 per US$1. However, russia’s Central Bank may draw on its accumulated reserves at any time to stabilise the exchange rate should it deem it necessary.

“The trade surplus is the main force behind russia’s ability to maintain macro-financial stability and pursue aggression. Not taxes, but having a positive trade balance. A drop in tax revenues will only lead to an increase in domestic borrowing or covert monetisation of the deficit, but will not affect the ability to build shadow import schemes and wage war.

As long as russia maintains a trade surplus, it doesn’t care whether its assets get frozen in the West. This step will remain somewhat symbolic for as long as the aggressor receives profits from international trade. Only a severe blow to foreign exchange earnings may inflict genuine damage on the aggressor,” said Viktor Koziuk, a former member of Ukraine’s National Bank Council.

Why are sanctions failing?

One of the primary reasons is that the sanctions took too long to emerge. Russia had a 6-12 month head start to prepare for the embargo: to find new markets, arrange for the supply of components, build infrastructure and gain political support in neutral countries.

The impression emerges that sanctions came into effect only after russia had found an alternative to the Western market. Even if it is impossible to replace the European market completely, alternative buyers mitigate the adverse effects on russia. If the shock of an abrupt cessation of supplies does not occur, then the sanctions lose their meaning.

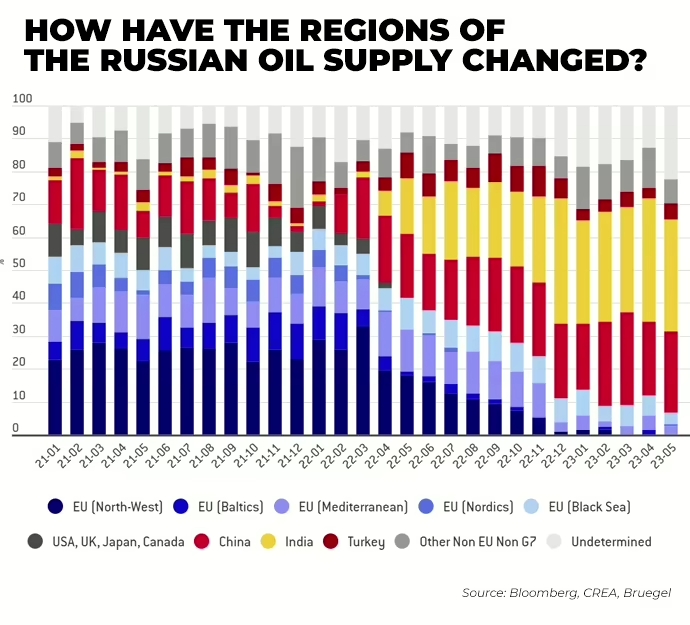

The geography of russian oil exports has changed significantly in just one year. The graph below outlines how russian oil flows have shifted to India, China and Türkiye just in time for the embargo to be imposed in early 2023. Therefore, russia’s production has hardly shrunk, and the aggressor continues to make money.

Shifting markets are forcing russia to offer huge discounts on its goods, albeit temporarily. For example, the discount on russian Urals oil [this oil brand is used as a reference for pricing – ed.] was US$30 per barrel at the beginning of russia’s invasion of Ukraine, whereas now it’s US$16. Things are heading towards a situation in which russian goods will gradually gain a foothold in Asia and become costlier.

The withdrawal of Western companies from the russian market was not a death sentence for the country either. Firstly, only a handful of companies have done so. Some of them continue to boost imports and saturate the empty russian market. Secondly, russia has managed to import some critical goods through third countries.

The russian business community has developed enough to master parallel imports. It’s when goods are imported not directly, but through third countries. With warehouses in Kazakhstan and well-established logistics, importing both permitted and prohibited goods into russia is possible.

This phenomenon has now become widespread. Many russian logistics companies already provide this service on a turnkey basis. This is more expensive than importing goods directly, but these schemes keep russian industry afloat. Russia can import car parts, machine tools, specialised chemicals, electronics, etc.

Electronic components for weapons also reach russia through a chain of intermediaries. Although Western countries prohibit their sale to russia, the chips still find their way to russian factories, particularly through Türkiye, China, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and other neutral countries.

Western partners themselves turn a blind eye to this. Robin Brooks, Chief Economist at the Institute of International Finance, noted that this year’s German exports to Kyrgyzstan are twice as high as Kyrgyz imports from Germany.

The difference in these figures is probably because some goods are sent directly to russia. Another part gets there through Kyrgyz intermediaries. The trade between Germany and Kyrgyzstan has abnormally increased tenfold, and no one sees anything suspicious in this.

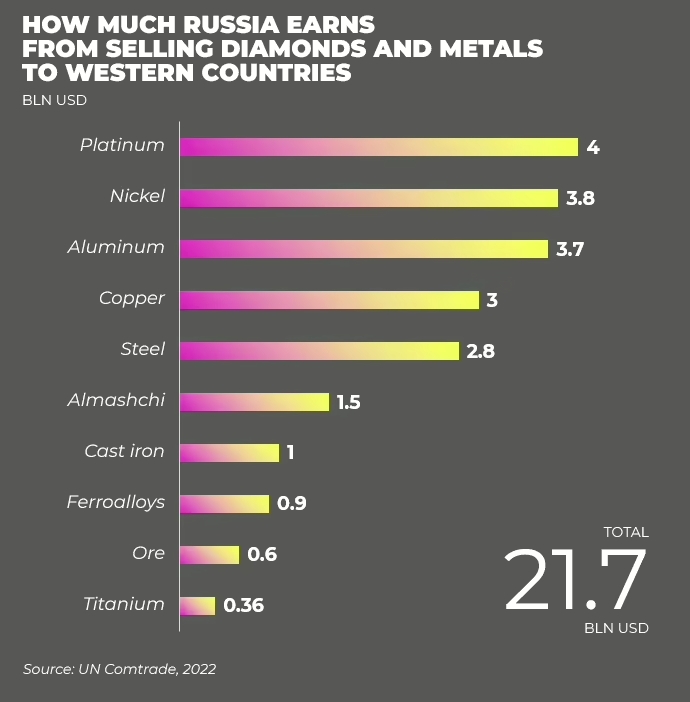

Not all russian goods are subject to sanctions. Apart from purely civilian and food products, there are a handful of exemptions: platinum, non-ferrous metals, diamonds, some steel products, etc. Western countries, mainly the European Union, are still buying all of these, boosting russian exports by at least US$20 billion.

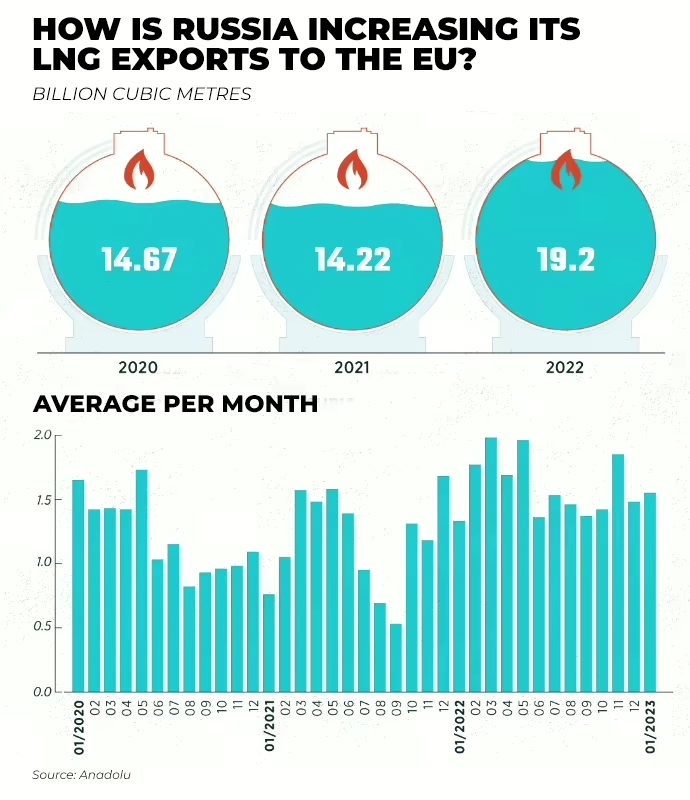

The energy embargo has turned into more of a compromise. Firstly, the EU still receives russian oil through one branch of the Druzhba Pipeline. Secondly, gas imports of both pipeline and liquefied natural gas are ongoing. Supplies of the latter are even growing. Combined with the gaps in the oil embargo, this brings tens of billions of dollars more to the aggressor’s coffers.

“The approach of Western countries to sanctions is sometimes less decisive than russia’s authoritarian and rapid actions, whose ability to adapt is greatly underestimated. The partners are also cautious about the potential economic impact of sanctions, which also slows down and dilutes the process,” said Vladyslav Vlasiuk, advisor to the Ukrainian President’s Office.

What will happen next?

The sanctions have reached a stage when every further restriction risks hitting both russia and Western countries. Nevertheless, the status quo will benefit only russia.

Pressure against russia has not stepped up in recent months, so the aggressor has plenty of time to find new markets and ways to circumvent sanctions. Consequently, russian revenues may remain at a comfortable level for the war to go on.

What can be done about this? Ukrainians have been proposing more radical methods since the beginning of the war. For example, the Ukrainian World Congress insists that trade with the aggressor should be completely stopped,and all russian banks should be disconnected from SWIFT [The Ukrainian World Congress is an international assembly of all Ukrainian public organisations in the diaspora – ed.].

A year and a half into the war, it has become clear that there will be no complete trade embargo against russia. The russian federation fully retains exports of food, fertilisers, access to the Asian market and certain technological and civilian goods. However, this does not mean that the aggressor has no weak points.

For example, russia’s gas exports are highly dependent on Europe, and it will take many years to shift them entirely to China. The trump card for substantially reducing russia’s gas production, one of its most significant sources of foreign exchange, is now in the hands of Western countries. The same goes for russia’s non-ferrous metals, platinum and diamonds, which Asian countries simply cannot provide.

There is still potential for toughening the technology embargo. This would require increasing diplomatic and sanction pressure on intermediaries, and strengthening control over components and their journey to the final consumer.

According to Vladyslav Vlasiuk, Ukraine is also promoting the idea of synchronising sanctions with all its allies and confiscating russian assets. The latter is the only chance to force the aggressor to feel the financial consequences of its actions.

If Ukraine’s Western allies want them to have a “second wind” in the fight against the aggressor, they must change their attitude to this war by working on their previous mistakes and taking new, more decisive sanctions against the kremlin.

This article was written as part of an ANTS project titled Russian Assets as a Source of Recovery of the Ukrainian Economy, implemented in cooperation with the National Democratic Institute (NDI) and with financial support from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).